As a companion to my other blog post on anarchism, I thought it would be fun to do a lighter post highlighting five anarchist comic book characters. For some reason, anarchist characters seem to get a fairer shake in comic books than in just about any mainstream medium. Perhaps that’s because several influential creators, like Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, and Alan Grant, are anarchists themselves. In any case, there are several anarchist comic book characters to choose from. I’m sure there are a lot more and if your favorite didn’t make the list, make a note of it in the comments section. The list is also partial to DC characters, because they’re the ones I know and love the most. These just happen to be my personal favorites and the ones that I think best fit the category. So without further ado, here’s the first of our anarchist anti-heroes …

1. V from V for Vendetta. This really comes as no surprise. V for Vendetta, by Alan Moore and David Lloyd was originally published in a UK anthology comic called Warrior in 1985, but never completed. In 1988, DC re-published the Warrior run and completed the series. Since then, it has been published as a graphic novel by DC’s Vertigo imprint and adapted into a feature film by Warner Bros. Pictures in 2006. V for Vendetta tells the story of a masked vigilante, V, and his female protege Evey Hammond, as they fight against a totalitarian regime in late 90’s Britain (changed to the 2020’s in the film). Moore, himself a self-professed anarchist, has stated that he intended the story as a contest between fascism and anarchy. There’s some interesting philosophical material here, including the question of whether violence is ever justified to achieve political ends. The book is also notable for capturing the ordinariness of fascism. The fascists are average people rather than comic book-type villains. This idea parallels Hannah Arendt’s notion of the ‘banality of evil.’ This sense is somewhat lost in the film; the villains, except for Finch, are less fleshed out, and more caricatured, than they appear in the book. The film is also less explicitly anarchist than the book, and Moore has distanced himself from any adaptation of his work, but the film is still worth watching in my opinion. It has some very memorable scenes and performances by the two leads, Hugo Weaving and Natalie Portman.

1. V from V for Vendetta. This really comes as no surprise. V for Vendetta, by Alan Moore and David Lloyd was originally published in a UK anthology comic called Warrior in 1985, but never completed. In 1988, DC re-published the Warrior run and completed the series. Since then, it has been published as a graphic novel by DC’s Vertigo imprint and adapted into a feature film by Warner Bros. Pictures in 2006. V for Vendetta tells the story of a masked vigilante, V, and his female protege Evey Hammond, as they fight against a totalitarian regime in late 90’s Britain (changed to the 2020’s in the film). Moore, himself a self-professed anarchist, has stated that he intended the story as a contest between fascism and anarchy. There’s some interesting philosophical material here, including the question of whether violence is ever justified to achieve political ends. The book is also notable for capturing the ordinariness of fascism. The fascists are average people rather than comic book-type villains. This idea parallels Hannah Arendt’s notion of the ‘banality of evil.’ This sense is somewhat lost in the film; the villains, except for Finch, are less fleshed out, and more caricatured, than they appear in the book. The film is also less explicitly anarchist than the book, and Moore has distanced himself from any adaptation of his work, but the film is still worth watching in my opinion. It has some very memorable scenes and performances by the two leads, Hugo Weaving and Natalie Portman.

2. Batman in The Dark Knight Returns. Since their inception, comic books have been about vigilantes. In taking the law into their own hands, these characters tacitly assert that their authority is on par with the ‘legitimate’ authority of the state. The state, the police, etc. are often portrayed as corrupt or incompetent. A good example is provided by another classic 80’s graphic novel, Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns. In that story, superheroes have been outlawed by the government because they’re essentially vigilantes. The only exception is Superman who has been co-opted by the US government and operates with its official sanction. When Batman comes out of retirement, Superman is called in to stop him. While the two duke it out, Batman accuses Superman of saying “yes to anyone with a badge — or a flag” of “selling out” and “giving them the power that should have been ours.” Batman recognizes that he’s become a “political liability” because he does what the so-called authorities can’t. Of course, this in and of itself is not an expression of anarchic philosophy, but it is consistent with several anarchic themes, especially the idea of the illegitimacy of external authority and of true power residing with the individual rather than the state.

2. Batman in The Dark Knight Returns. Since their inception, comic books have been about vigilantes. In taking the law into their own hands, these characters tacitly assert that their authority is on par with the ‘legitimate’ authority of the state. The state, the police, etc. are often portrayed as corrupt or incompetent. A good example is provided by another classic 80’s graphic novel, Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns. In that story, superheroes have been outlawed by the government because they’re essentially vigilantes. The only exception is Superman who has been co-opted by the US government and operates with its official sanction. When Batman comes out of retirement, Superman is called in to stop him. While the two duke it out, Batman accuses Superman of saying “yes to anyone with a badge — or a flag” of “selling out” and “giving them the power that should have been ours.” Batman recognizes that he’s become a “political liability” because he does what the so-called authorities can’t. Of course, this in and of itself is not an expression of anarchic philosophy, but it is consistent with several anarchic themes, especially the idea of the illegitimacy of external authority and of true power residing with the individual rather than the state.

3. Anarky (First Appearance, Detective Comics #608, 1989). Over the years, vigilante superheroes have faced one of two fates: having their edge dulled by mainstream publishers or devolving into fascist characters who are obsessed with order at the expense of liberty. Both of these fates have befallen Batman at various points in his history. He became an establishment-friendly character in the 50’s and 60’s and then, after his revamp in the 80’s, became a paranoid, fascist control freak who would seem very much at home in a surveillance state or a post-Patriot Act world. To his credit, Christopher Nolan touched on these themes in his Dark Knight trilogy, in addition to asking questions about the legitimacy of authority. To shake things up, and introduce a counterpoint to this version of Batman, Alan Grant and Norm Breyfogle created the character Anarky in 1989. Clearly inspired by V, Anarky started out as a Batman ‘villain’ but later starred in his own miniseries as an ‘anti-hero.’ Grant, who is a member of the British Anarchist Society, created the character to explore his own political philosophy. The character received a lukewarm reaction in the United States, although Grant said in an interview that he “received quite a few letters (especially from philosophy students) saying the comic had changed their entire mindset.” Breyfogle also acknowledged the character’s limited appeal saying, “It has some diehard fans [in some segments of the industry]. But, DC doesn’t seem to want to do anything with him. Maybe it’s because of his anti-authoritarian philosophy, a very touchy subject in today’s world. Alan is very much anti-authoritarian.” Anarky has since appeared in Robin and as a major villain in the recent Beware the Batman animated series, however his portrayal in both outings leaves much to be desired. Still, the fact that mainstream comics has a place for this character at all is quite remarkable.

3. Anarky (First Appearance, Detective Comics #608, 1989). Over the years, vigilante superheroes have faced one of two fates: having their edge dulled by mainstream publishers or devolving into fascist characters who are obsessed with order at the expense of liberty. Both of these fates have befallen Batman at various points in his history. He became an establishment-friendly character in the 50’s and 60’s and then, after his revamp in the 80’s, became a paranoid, fascist control freak who would seem very much at home in a surveillance state or a post-Patriot Act world. To his credit, Christopher Nolan touched on these themes in his Dark Knight trilogy, in addition to asking questions about the legitimacy of authority. To shake things up, and introduce a counterpoint to this version of Batman, Alan Grant and Norm Breyfogle created the character Anarky in 1989. Clearly inspired by V, Anarky started out as a Batman ‘villain’ but later starred in his own miniseries as an ‘anti-hero.’ Grant, who is a member of the British Anarchist Society, created the character to explore his own political philosophy. The character received a lukewarm reaction in the United States, although Grant said in an interview that he “received quite a few letters (especially from philosophy students) saying the comic had changed their entire mindset.” Breyfogle also acknowledged the character’s limited appeal saying, “It has some diehard fans [in some segments of the industry]. But, DC doesn’t seem to want to do anything with him. Maybe it’s because of his anti-authoritarian philosophy, a very touchy subject in today’s world. Alan is very much anti-authoritarian.” Anarky has since appeared in Robin and as a major villain in the recent Beware the Batman animated series, however his portrayal in both outings leaves much to be desired. Still, the fact that mainstream comics has a place for this character at all is quite remarkable.

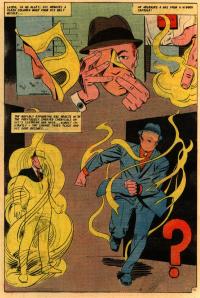

4. The Question (First appearance, Blue Beetle #67, Charlton Comics) The Question was created by Steve Ditko, co-creator of Spider-man and creator of Doctor Strange at Marvel and, less famously, Hawk and Dove and the Creeper, at DC. In between, Ditko worked for a company called Charlton Comics where he created The Question, a vigilante who dons a faceless mask and metes out justice. Ditko was also a devotee of Ayn Rand’s philosophy of Objectivism. In fact, his commitment to this philosophy may have contributed to his leaving Marvel over ‘creative differences’ with writer and editor Stan Lee. The Question embodies Ditko’s Objectivist sympathies (as did his earlier creation, Mr. A). The character, both in his civilian guise as Vic Sage and his heroic alter ego, presents man as master of his own destiny and the only legitimate authority. DC later acquired the Charlton characters, including The Question, and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons had originally planned to use him in Watchmen, however, editorial intervention nixed that idea. However, the character Rorschach is based on Ditko’s creation. The character has undergone several changes over the years: Dennis O’Neil took him away from his Randian roots and made him a Zen Buddhist. In the current comics continuity (although who can keep up with that nowadays?), Rene Montoya, a female (and lesbian) former Gotham City police detective has taken up the mantle of The Question (after Vic Sage’s death in 52). But my favorite version is still Ditko’s. The character was also interpreted brilliantly in the Justice League Unlimited animated series and played a major role in the first season story arch, especially the episode ‘Question Authority.’ You can’t find a better statement of anarchism than that!

4. The Question (First appearance, Blue Beetle #67, Charlton Comics) The Question was created by Steve Ditko, co-creator of Spider-man and creator of Doctor Strange at Marvel and, less famously, Hawk and Dove and the Creeper, at DC. In between, Ditko worked for a company called Charlton Comics where he created The Question, a vigilante who dons a faceless mask and metes out justice. Ditko was also a devotee of Ayn Rand’s philosophy of Objectivism. In fact, his commitment to this philosophy may have contributed to his leaving Marvel over ‘creative differences’ with writer and editor Stan Lee. The Question embodies Ditko’s Objectivist sympathies (as did his earlier creation, Mr. A). The character, both in his civilian guise as Vic Sage and his heroic alter ego, presents man as master of his own destiny and the only legitimate authority. DC later acquired the Charlton characters, including The Question, and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons had originally planned to use him in Watchmen, however, editorial intervention nixed that idea. However, the character Rorschach is based on Ditko’s creation. The character has undergone several changes over the years: Dennis O’Neil took him away from his Randian roots and made him a Zen Buddhist. In the current comics continuity (although who can keep up with that nowadays?), Rene Montoya, a female (and lesbian) former Gotham City police detective has taken up the mantle of The Question (after Vic Sage’s death in 52). But my favorite version is still Ditko’s. The character was also interpreted brilliantly in the Justice League Unlimited animated series and played a major role in the first season story arch, especially the episode ‘Question Authority.’ You can’t find a better statement of anarchism than that!

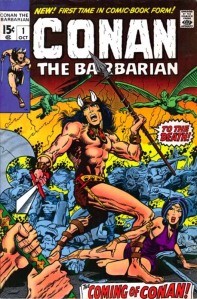

5. Conan the Barbarian. Originally created by Robert E. Howard and published in the pages of the pulp magazine, Weird Tales, Conan also enjoyed success in Marvel Comics in the 70’s. The creative team of Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith effortlessly captured the magical Hyborian world of the wandering barbarian. They also adapted several of Howard’s classic Conan tales. These stories deftly handle Howard’s conflict between barbarism and civilization. As his stories make clear, Howard himself favored the former. In one of his stories, a character says (paraphrased from memory) “Barbarism is the natural state of man. Civilization is an accident.” Howard seemed to revel in his portrayal of Conan as ‘a noble savage.’ The character forges his own destiny and respects no authority. Although painting a romantic picture, the world of Conan is harsh and violent and the only law comes at the point of a sword (or in the case of Kull, the edge of an axe). Also, Conan eventually becomes King of Aquilonia and absolute monarchy is about as far from anarchy as you can get! Although this might disqualify him as an anarchist character for some, the Conan stories often present a man without a country, who refuses to be ruled by another. It also presents us with a number of challenges that those establishing a stateless society would have to solve, and hopefully more peacefully than Conan does. This exercise in imagination — what might a stateless society look like? — is valuable when thinking about political philosophy.

5. Conan the Barbarian. Originally created by Robert E. Howard and published in the pages of the pulp magazine, Weird Tales, Conan also enjoyed success in Marvel Comics in the 70’s. The creative team of Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith effortlessly captured the magical Hyborian world of the wandering barbarian. They also adapted several of Howard’s classic Conan tales. These stories deftly handle Howard’s conflict between barbarism and civilization. As his stories make clear, Howard himself favored the former. In one of his stories, a character says (paraphrased from memory) “Barbarism is the natural state of man. Civilization is an accident.” Howard seemed to revel in his portrayal of Conan as ‘a noble savage.’ The character forges his own destiny and respects no authority. Although painting a romantic picture, the world of Conan is harsh and violent and the only law comes at the point of a sword (or in the case of Kull, the edge of an axe). Also, Conan eventually becomes King of Aquilonia and absolute monarchy is about as far from anarchy as you can get! Although this might disqualify him as an anarchist character for some, the Conan stories often present a man without a country, who refuses to be ruled by another. It also presents us with a number of challenges that those establishing a stateless society would have to solve, and hopefully more peacefully than Conan does. This exercise in imagination — what might a stateless society look like? — is valuable when thinking about political philosophy.

Well, there you have it. I hope you enjoyed my round-up of anarchist comic book characters. There are many more I could’ve included, especially villains, but I tried to pick characters that are treated somewhat sympathetically. Thanks for reading and be sure to include any characters I missed in the comments below!

After the false start of The Motion Picture, the Star Trek franchise got back on track with The Wrath of Khan. In my opinion, this is the best of the Star Trek films. The main reason, I think, is that there’s real continuity between this movie and the TV series. TWOK makes a real contribution to the Star Trek canon and cements the show’s and character’s iconic status in the popular consciousness. The fact that the recent entry, Into Darkness, could do no better than reference TWOK is evidence of its cultural endurance, even among non-Trekkers. For example, how many times has Shatner’s famous “KHAAAAAAAN!” yell been emulated or parodied? Incidentally, when Zachary Quinto did so in Into Darkness, I laughed. I don’t think the filmmakers intended it to be comedic, but it took me out of the movie. But I digress.

After the false start of The Motion Picture, the Star Trek franchise got back on track with The Wrath of Khan. In my opinion, this is the best of the Star Trek films. The main reason, I think, is that there’s real continuity between this movie and the TV series. TWOK makes a real contribution to the Star Trek canon and cements the show’s and character’s iconic status in the popular consciousness. The fact that the recent entry, Into Darkness, could do no better than reference TWOK is evidence of its cultural endurance, even among non-Trekkers. For example, how many times has Shatner’s famous “KHAAAAAAAN!” yell been emulated or parodied? Incidentally, when Zachary Quinto did so in Into Darkness, I laughed. I don’t think the filmmakers intended it to be comedic, but it took me out of the movie. But I digress. Okay, so I couldn’t resist a bad pun in the title. Seriously though, it summarizes my problem with the first feature length Star Trek film: not much happens in this movie. When something finally does happen, it isn’t very interesting. There’s not even enough content here for a filler episode of the original series. Now, I can imagine some readers saying ‘You just don’t get deliberately paced, conceptual sci-fi. Go back to watching the Abrams-verse if you can’t handle the real deal.’ That might be a valid criticism if it weren’t for the fact that I have serious problems with the action-oriented reboot as well. No, the problem isn’t that I don’t appreciate philosophical, cerebral sci-fi. I do. I like 2001, Solaris, Moon, even Prometheus (which a lot of people hated). The problem with The Motion Picture isn’t that it aspires to be philosophical; the problem is that it aspires and fails. It also fails to be entertaining which is a cardinal sin for any fictional medium, clever or otherwise.

Okay, so I couldn’t resist a bad pun in the title. Seriously though, it summarizes my problem with the first feature length Star Trek film: not much happens in this movie. When something finally does happen, it isn’t very interesting. There’s not even enough content here for a filler episode of the original series. Now, I can imagine some readers saying ‘You just don’t get deliberately paced, conceptual sci-fi. Go back to watching the Abrams-verse if you can’t handle the real deal.’ That might be a valid criticism if it weren’t for the fact that I have serious problems with the action-oriented reboot as well. No, the problem isn’t that I don’t appreciate philosophical, cerebral sci-fi. I do. I like 2001, Solaris, Moon, even Prometheus (which a lot of people hated). The problem with The Motion Picture isn’t that it aspires to be philosophical; the problem is that it aspires and fails. It also fails to be entertaining which is a cardinal sin for any fictional medium, clever or otherwise.

1. Must There Be A Superman? (Superman #247, Jan 1972) Superman is a god-like figure, a secular messiah, and for most of his history, writers never questioned whether or not Superman’s presence on Earth was good for humanity. However, Elliot S! Maggin did just that in ‘Must There Be A Superman?’ In the story, The Guardians of the Universe (and founders of the Green Lantern Corps) confront Superman with the possibility that he is holding back humanity’s progress. They argue that humans have become too reliant on Superman and have failed to solve their own problems. Superman takes this idea to heart (at least for the duration of the issue) and experiments with a more hands-off approach. The details of the adventure are less important to me than the question it raises. If a god-like being did intervene in our world in seemingly beneficial ways, would that be an unqualified good? Nietzsche, who originally coined the term ‘superman’ (Übermensch), certainly didn’t think so.

1. Must There Be A Superman? (Superman #247, Jan 1972) Superman is a god-like figure, a secular messiah, and for most of his history, writers never questioned whether or not Superman’s presence on Earth was good for humanity. However, Elliot S! Maggin did just that in ‘Must There Be A Superman?’ In the story, The Guardians of the Universe (and founders of the Green Lantern Corps) confront Superman with the possibility that he is holding back humanity’s progress. They argue that humans have become too reliant on Superman and have failed to solve their own problems. Superman takes this idea to heart (at least for the duration of the issue) and experiments with a more hands-off approach. The details of the adventure are less important to me than the question it raises. If a god-like being did intervene in our world in seemingly beneficial ways, would that be an unqualified good? Nietzsche, who originally coined the term ‘superman’ (Übermensch), certainly didn’t think so.

5. All-Star Superman (All-Star Superman, #1 — 12 Nov 2005 — Oct 2008) I should begin with a confession: I’m not a big Grant Morrison fan. Within continuity, his work has a tendency to become a muddled mess, but when his imagination is given free reign, the result is arguably one of the best Superman stories in the character’s long history. All-Star is in the same spirit as Moore’s ‘Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow.’ It proposes a hypothetical conclusion to the Superman saga, one that not only brilliantly situates Superman within his own mythology, but within mythology more generally. It is a Joseph Campbell-esque tale of the trajectory of a hero. The story is full of imagination and manages to pay homage to the character’s past while simultaneously bringing a fresh perspective (something that comic books and pop culture in general doesn’t do very often). It also manages to be both a good introduction to the character for new readers and a rewarding experience for long-time fans.

5. All-Star Superman (All-Star Superman, #1 — 12 Nov 2005 — Oct 2008) I should begin with a confession: I’m not a big Grant Morrison fan. Within continuity, his work has a tendency to become a muddled mess, but when his imagination is given free reign, the result is arguably one of the best Superman stories in the character’s long history. All-Star is in the same spirit as Moore’s ‘Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow.’ It proposes a hypothetical conclusion to the Superman saga, one that not only brilliantly situates Superman within his own mythology, but within mythology more generally. It is a Joseph Campbell-esque tale of the trajectory of a hero. The story is full of imagination and manages to pay homage to the character’s past while simultaneously bringing a fresh perspective (something that comic books and pop culture in general doesn’t do very often). It also manages to be both a good introduction to the character for new readers and a rewarding experience for long-time fans.